- Home

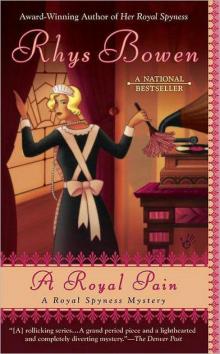

- A Royal Pain

Rhys Bowen_Royal Spyness 02

Rhys Bowen_Royal Spyness 02 Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Berkley Prime Crime Mysteries by Rhys Bowen

Royal Spyness Mysteries

HER ROYAL SPYNESS

A ROYAL PAIN

Constable Evans Mysteries

EVANS ABOVE

EVAN HELP US

EVANLY CHOIRS

EVAN AND ELLE

EVAN CAN WAIT

EVANS TO BETSY

EVAN ONLY KNOWS

EVAN’S GATE

EVAN BLESSED

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

This book is an original publication of The Berkley Publishing Group.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2008 by Janet Quin-Harkin.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

The name BERKLEY PRIME CRIME and the BERKLEY PRIME CRIME design are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

eISBN : 978-1-4406-2952-5

1. Aristocracy (Social class)—Fiction. 2. London (England)—History—20th century—

Fiction. I. Title.

PR6052.O848R69 2008

823’.914—dc22 2008010406

http://us.penguingroup.com

This book is dedicated to my three princesses:

Elizabeth, Meghan and Mary;

and to my princes: Sam and T. J.

Notes and Acknowledgments

This is a work of fiction. While several members of the British royal family appear as themselves in the book, there was no Princess Hannelore of Bavaria and no Lady Georgiana.

On a historical note: Europe at that time was in turmoil with communists and fascists vying for control of Germany, left bankrupt and dispirited after the first great war. In England communism was making strides among the working classes and left-wing intellectuals. At the other extreme Oswald Mosley was leading a group of extreme fascists called the Blackshirts. Skirmishes and bloody battles between the two were frequent in London.

A special acknowledgment to the Misses Hedley, Jensen, Reagan and Danika, of Sonoma, California, who make cameo appearances in this book.

And thanks, as always, to my splendid support group at home: Clare, Jane and John; as well as my equally splendid support group in New York: Meg, Kelly, Jackie and Catherine.

Chapter 1

Rannoch House

Belgrave Square

London W.1.

Monday, June 6, 1932

The alarm clock woke me this morning at the ungodly hour of eight. One of my nanny’s favorite sayings was “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.” My father did both and look what happened to him. He died, penniless, at forty-nine.

In my experience there are only two good reasons to rise with the dawn: one is to go hunting and the other to catch the Flying Scotsman from Edinburgh to London. I was about to do neither. It wasn’t the hunting season and I was already in London.

I fumbled for the alarm on the bedside table and battered it into silence.

“Court circular, June 6,” I announced to a nonexistent audience as I stood up and pulled back the heavy velvet curtains. “Lady Georgiana Rannoch embarks on another hectic day of social whirl. Luncheon at the Savoy, tea at the Ritz, a visit to Scapparelli for a fitting of her latest ball gown, then dinner and dancing at the Dorchester—or none of the above,” I added. To be honest it had been a long time since I had any events on my social calendar and my life had never been a mad social whirl. Almost twenty-two years old and not a single invitation sitting on my mantelpiece. The awful thought struck me that I should accept that I was over the hill and destined to be a spinster for life. Maybe all I had to look forward to was the queen’s suggestion that I become lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria’s one surviving daughter—who is also my great-aunt and lives out in deepest Gloucestershire. Years ahead of walking the Pekinese and holding knitting wool danced before my eyes.

I suppose I should introduce myself before I go any further: I am Victoria Georgiana Charlotte Eugenie of Glen Garry and Rannoch, known to my friends as Georgie. I am of the house of Windsor, second cousin to King George V, thirty-fourth in line to the throne, and at this moment I was stony broke.

Oh, wait. There was another option for me. It was to marry Prince Siegfried of Romania, in the Hohenzollen-Sigmaringen line—for whom my private nickname was Fish-face. That subject hadn’t come up recently, thank God. Maybe other people had also found out that he has a predilection for boys.

It was clearly going to be one of those English summer days that makes one think of rides along leafy country lanes, picnics in the meadow with strawberries and cream, croquet and tea on the lawn. Even in central London birds were chirping madly. The sun was sparkling from the windows across the square. A gentle breeze was stirring the net curtains. The postman was whistling as he walked around the square. And what did I have before me?

“Oh, golly,” I exclaimed as I suddenly remembered the reason for the alarm clock

and leaped into action. I was expected at a residence on Park Lane. I washed, dressed smartly and went downstairs to make some tea and toast. You can see how wonderfully domesticated I’d become in two short months. When I bolted from our castle in Scotland back in April, I didn’t even know how to boil water. Now I can manage baked beans and an egg. For the first time in my life I was living with no servants, having no money to pay them. My brother, the Duke of Glen Garry and Rannoch, usually known as Binky, had promised to send me a maid from our Scottish estate, but so far none had materialized. I suspect that no God-fearing, Presbyterian Scottish mother would let her daughter loose in the den of iniquity that London is perceived to be. As for paying for me to hire a maid locally—well, Binky is as broke as I. You see, when our father shot himself after the crash of ’29, Binky inherited the estate and was saddled with the most horrendous death duties.

So I have managed thus far servantless, and frankly, I’m jolly proud of myself. The kettle boiled. I made my tea, slathered Cooper’s Oxford marmalade on my toast (yes, I know I was supposed to be economizing but there are standards below which one just can’t sink) and brushed away the crumbs hastily as I put on my coat. It was going to be too warm for any kind of jacket, but I couldn’t risk anyone seeing what I was wearing as I walked through Belgravia—the frightfully upper-crust part of London just south of Hyde Park where our town house is situated.

A chauffeur waiting beside a Rolls saluted smartly to me as I passed. I held my coat tightly around me. I crossed Belgrave Square, walked up Grosvenor Cresent and paused to look longingly at the leafy expanse of Hyde Park before I braved the traffic across Hyde Park Corner. I heard the clip-clop of hooves and a pair of riders came out of Rotten Row. The girl was riding a splendid gray and was smartly turned out in a black bowler and well-cut hacking jacket. Her boots were positively gleaming with polish. I looked at her enviously. Had I stayed home in Scotland that could have been me. I used to ride every morning with my brother. I wondered if my sister-in-law, Fig, was riding my horse and ruining its mouth. She was inclined to be heavy-handed with the reins, and she weighed a good deal more than I. Then I noticed other people loitering on the corner. Not so well turned out, these men. They carried signs or sandwich boards: I need a job. Will work for food. Not afraid of hard work.

I had grown up sheltered from the harsh realities of the world. Now I was coming face-to-face with them on a daily basis. There was a depression going on and people were lining up for bread and soup. One man who stood beneath Wellington’s Arch had a distinguished look to him, well-polished shoes, coat and tie. In fact he was wearing medals. Wounded on Somme. Any kind of employment considered. I could read in his face his desperation and his repugnance at having to do this and wished that I had the funds to hire him on the spot. But essentially I was in the same boat as most of them.

Then a policeman blew his whistle, traffic stopped and I sprinted across the street to Park Avenue. Number 59 was fairly modest by Park Lane standards—a typical Georgian house of the smart set, redbrick with white trim, with steps leading up to the front door and railings around the well that housed the servants’ quarters below stairs. Not dissimilar to Rannoch House although our London place is a good deal larger and more imposing. Instead of going up to the front door, I went gingerly down the dark steps to the servants’ area and located the key under a flowerpot. I let myself in to a dreadful dingy hallway in which the smell of cabbage lingered.

All right, so now you know my dreadful secret. I’ve been earning money by cleaning people’s houses. My advertisement in the Times lists me as Coronet Domestics, as recommended by Lady Georgiana of Glen Garry and Rannoch. I don’t do any proper heavy cleaning. No scrubbing of floors or, heaven forbid, lavatory bowls. I wouldn’t have a clue where to begin. I undertake to open up the London houses for those who have been away at their country estates and don’t want to go to the added expense and nuisance of sending their servants ahead of them to do this task. It involves whisking off dust sheets, making beds, sweeping and dusting. That much I can do without breaking anything too often—since another thing you should know about me is that I am prone to the occasional episode of clumsiness.

It is a job sometimes fraught with danger. The houses I work in are owned by people of my social set. I’d die of mortification if I bumped into a fellow debutante or, even worse, a dance partner, while on my hands and knees in a little white cap. So far only my best friend, Belinda Warburton-Stoke, and an unreliable rogue called Darcy O’Mara know about my secret. And the least said about him, the better.

Until I started this job, I had never given much thought to how the other half lives. My own recollections of going below stairs to visit the servants all centered around big warm kitchens with the scent of baking and being allowed to help roll out the dough and lick the spoon. I found the cleaning cupboard and helped myself to a bucket and cloths, feather duster, and a carpet sweeper. Thank heavens it was summer and no fires would be required in the bedrooms. Carrying coal up three flights of stairs was not my favorite occupation, nor was venturing into what my grandfather called the coal’ole to fill the scuttles. My grandfather? Oh, sorry. I suppose I hadn’t mentioned him. My father was first cousin to King George, and Queen Victoria’s grandson, but my mother was an actress from Essex. Her father still lives in Essex, in a little house with gnomes in the front garden. He’s a genuine Cockney and a retired policeman. I absolutely adore him. He’s the one person to whom I can say absolutely anything.

At the last second I remembered to retrieve my maid’s cap from my coat pocket and jammed it over my unruly hair. Maids are never seen without their caps. I pushed open the baize door that led to the main part of the house and barreled into a great pile of luggage, which promptly fell over with a crash. Who on earth thought of piling luggage against the door to the servants’ quarters? Before I could pick up the strewn suitcases there was a shout and an elderly woman dressed head to toe in black appeared from the nearest doorway, waving a stick at me. She was still wearing an old-fashioned bonnet tied under her chin and a traveling cloak. An awful thought struck me that I had mistaken the number, or written it down wrongly, and I was in the wrong house.

“What is happening?” she demanded in French. She glanced at my outfit. “Vous êtes la bonne?” Asking “Are you the maid?” in French was rather a strange way to greet a servant in London, where most servants have trouble with proper English. Fortunately I was educated in Switzerland and my French is quite good. I replied that I was indeed the maid, sent to open up the house by the domestic service, and I had been told that the occupants would not arrive until the next day.

“We came early,” she said, still in French. “Jean-Claude drove us from Biarritz to Paris in the motorcar and we caught the overnight train.”

“Jean-Claude is the chauffeur?” I asked.

“Jean-Claude is the Marquis de Chambourie,” she said. “He is also a racing driver. We made the trip to Paris in six hours.” Then she realized she was talking to a housemaid. “How is it that you speak passable French for an English person?” she asked.

I was tempted to say that I spoke jolly good French, but instead I mumbled something about traveling abroad with the family on the Côte D’Azur.

“Fraternizing with French sailors, I shouldn’t be surprised,” she muttered.

“And you, you are Madame’s housekeeper?” I asked.

“I, my dear young woman, am the Dowager Countess Sophia of Liechtenstein,” she said, and in case you’re wondering why a countess of a German-speaking country was talking to me in French, I should point out that high-born ladies of her generation usually spoke French, no matter what their native tongue was. “My maid is attempting to make a bedroom ready for me,” she continued with a wave of her hand up the stairs. “My housekeeper and the rest of my staff will arrive tomorrow by train as planned. Jean-Claude drives a two-seater motorcar. My maid had to perch on the luggage. I understand it was most disagreeable for her.” She paused to scowl

at me. “And it is most disagreeable for me to have nowhere to sit.”

I wasn’t quite sure of the protocol of the court of Liechtenstein and how one addressed a dowager countess of that land, but I’ve discovered that when in doubt, guess upward. “I’m sorry, Your Highness, but I was told to come today. Had I known that you had a relative who was a racing driver, I would have prepared the house yesterday.” I tried not to grin as I said this.

She frowned at me, trying to ascertain whether I was being cheeky or not, I suspect. “Hmmph,” was all she could manage.

“I will remove the covers from a comfortable chair for Your Highness,” I said, going through into a large dark drawing room and whisking the cover off an armchair, sending a cloud of dust into the air. “Then I will make ready your bedroom first. I am sure the crossing was tiring and you need a rest.”

“What I want is a good hot bath,” she said.

Ah, that might be a slight problem, I thought. I had seen my grandfather lighting the boiler at Rannoch House but I had no personal experience of doing anything connected to boilers. Maybe the countess’s maid was more familiar with such things.

Someone would have to be. I wondered how to say “boilers are not in my contract” in French.

“I will see what can be done,” I said, bowed and backed out of the room. Then I grabbed my cleaning supplies and climbed the stairs. The maid looked about as old and bad-tempered as the countess, which was understandable if she’d had to ride all the way from Biarritz perched on top of the luggage. She had chosen the best bedroom, at the front of the house overlooking Hyde Park, and had already opened the windows and taken the dust covers off the furniture. I tried speaking to her in French, then English, but it seemed that she only spoke German. My German was not up to more than “I’d like a glass of mulled wine,” and “Where is the ski lift?” So I pantomimed that I would make the bed. She looked dubious. We found sheets and made it between us. This was fortunate as she was most particular about folding the corners just so. She also rounded up about a dozen more blankets and eiderdowns from bedrooms on the same floor, as apparently the countess felt the cold in England. That much I could understand.

Rhys Bowen_Royal Spyness 02

Rhys Bowen_Royal Spyness 02